What Happens with Trauma…..

When danger is perceived—whether from the environment or the worries in our minds—the body is wired to respond automatically in the following ways:

The sympathetic nervous system goes into full alert, sending stress hormones to the respiratory, cardiovascular, and muscular systems, preparing us to either fight or flee. The neocortex (the thinking part of the brain) shuts down, including Broca’s area, which governs speech. This happens because instinct is faster than thought, and in a dangerous situation, forming words and contemplating choices is a luxury we cannot afford. This is also why, when we feel threatened, it becomes difficult to communicate—both to accurately hear information and to find the right words to express ourselves.

When confronted with such situations, all mammals—including humans—experience the fight–or–flight freeze response. This is the body’s natural reaction to danger: a stress response that helps us react to perceived threats, such as an oncoming car or a dark alley.

This response triggers immediate hormonal and physiological changes that enable us to act quickly and protect ourselves. It’s a survival instinct biologically developed by our ancient ancestors.

- Fight or flight is an active defence response. Your heart rate increases, boosting oxygen flow to major muscles (you’re about to need them). Pain perception drops (it’s going to hurt), and hearing sharpens (to detect danger). These changes help you respond rapidly and appropriately.

- Freezing is fight or flight on hold—a further preparation to protect yourself. Also known as reactive immobility or attentive immobility, it is involuntary. It involves similar physiological changes, but instead of acting, you remain completely still, ready for the next move.

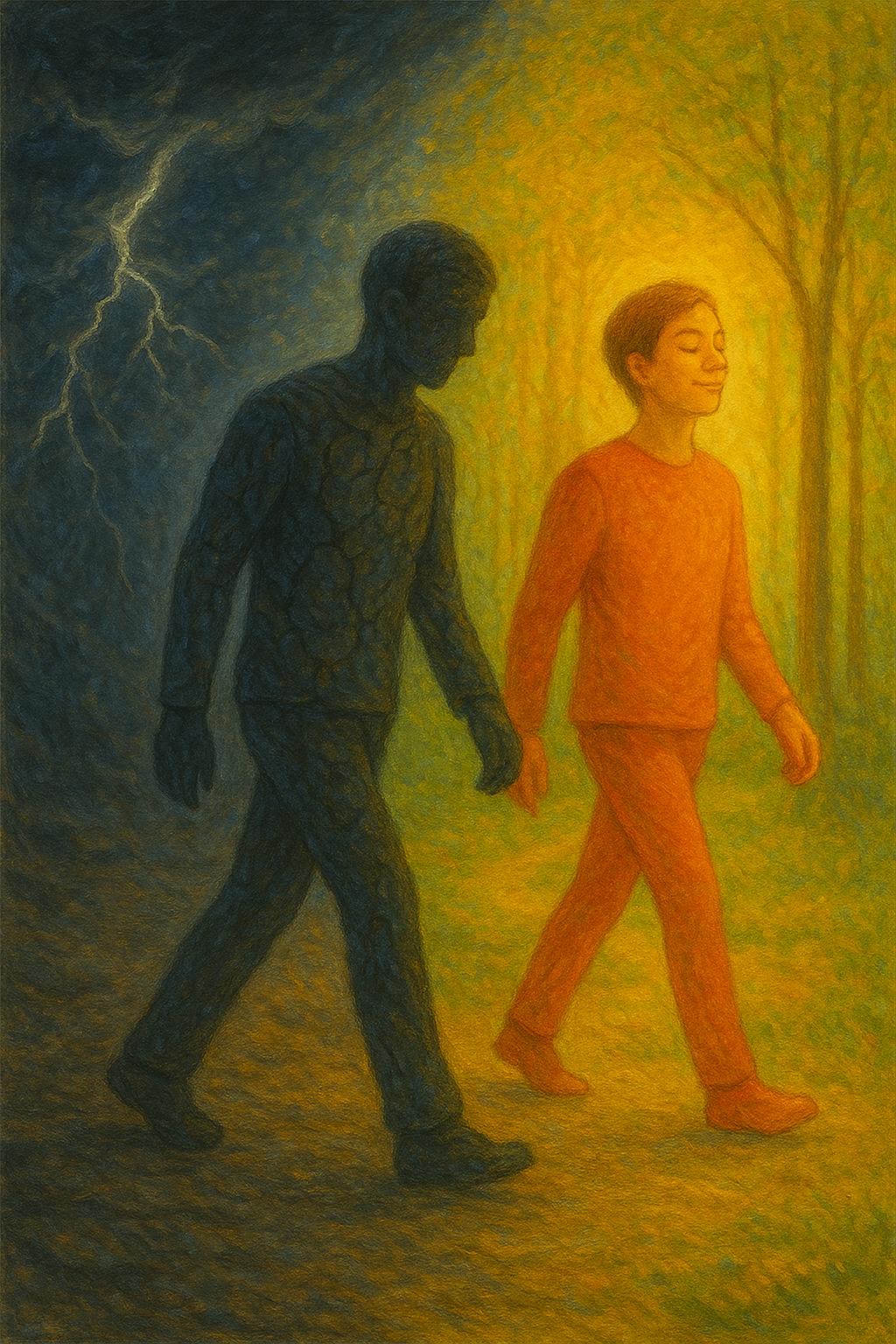

Additionally, endorphins are released to manage anticipated pain, and the mind may dissociate from the body and the experience. This means the trauma has overwhelmed our capacity to cope. Trauma doesn’t have to stem from physical violence or major disasters—it can be anything that overwhelms the mind, body, or spirit and causes shutdown.

When this happens, the traumatic experience is encoded in implicit memory—not as a coherent story, but as fragmented pieces: images, thoughts, sounds, smells, physical sensations, and highly charged emotions.

Once the threat has passed, all mammals—including humans—need to discharge the energy physically through shaking, pacing, running, or crying. Humans also have the added task of moving the experience from implicit memory into explicit memory by adding words and creating a meaningful narrative. This narrative helps describe not only the experience but also how we see ourselves—what we believe about life and ourselves after the event.

Implicit memory has no sense of time. This means that when something reminds us of a traumatic incident, it is not just remembered—it is re-experienced. Stress hormones are released again. The sympathetic nervous system goes into alarm mode, the heart races, muscles tense, and the neocortex goes offline. Instead of remembering the past, it feels like it’s happening now. This is what defines a traumatic memory.

Traumatic memory results from the experience being blocked from moving from implicit to explicit memory—especially when the freeze response occurs. The mind continues to attempt healing by “knocking on the door” of the conscious, verbal brain. But when that part of the brain “looks out the window,” it sees a network of upsetting neural memories and barricades the door instead of inviting them in.

Intrusion symptoms may include:

☢ Trauma flashbacks

☢ Uncomfortable feelings with no apparent source

☢ Emotional overreactions

☢ Physical sensations that don’t make rational sense

☢ Anxiety about performance despite being prepared

☢ Negative self-talk

☢ Slips of speech

☢ Self-sabotaging behaviours

These are often implicit memory “knocking.” Avoidance symptoms—such as dissociation, self-destructive behaviours, isolation, and denial—are the neocortex’s attempt to ignore these “unwelcome visitors.”

It takes an enormous amount of psychological and physical energy to keep this door shut and guarded. EMDR works by helping implicit and explicit memory communicate while keeping the body relaxed. The traumatic incident becomes narrative history instead of wordless terror without end.

Research shows that writing and journaling can also support healing. However, for many trauma survivors, this is often too painful. Trauma and grief are most effectively resolved when the story is shared with at least one other person. We seem to be wired to need a supportive other to bear witness. Sadly, trauma often renders survivors unable to speak about their experience, adding isolation and loneliness to their pain.

After Eye Movement Therapy, people often report feeling more at peace with themselves—and more connected to others.